I competed in the

3 minute thesis (3MT) competition recently and it was such a great experience that I thought I would share it here.

Sitting down and trying to summarise 3 years of work into 3 mins is a very hard task, especially when trying to make it accessible to a general audience. It really makes you take a step back and remember what's important about your work. Why SHOULD people care about what I do and find it interesting?

I know this has all been said before but it is so vital to be able to explain your research quickly and accessibly. I think this experience will not only help me tell my Grandma what I do, but will be a huge advantage when I want to explain my research to future collaborators or employers.

The 3MT experience was especially useful for me because I had a fair amount of media exposure a few weeks ago as a result of a paper I published. I had so many radio interviews and my first stint on live TV which was petrifying. But whenever my brain froze on a difficult (or completely normal) question, little snippets of my 3MT came back to me and mercifully gave me something intelligent to say.

I also learned that I have to stop putting my hands in my pockets when I give presentations.

So here is what I said, and why I think my research is important!

|

Photo by Glenda Wardle @desert_ecology

|

We live in

a world that has changed drastically in the last 100.

Urbanisation

creates novel environments with completely different conditions to those in

which most animals evolved to survive in.

As a

result, the majority of animals are driven to extinction in human inhabited

areas.

But there

are some animals, called urban exploiters, which can survive and even thrive in cities.

Those of us

living in cities see urban exploiters such as pigeons and crows every day.

But did you

know that these urban dwellers may be showing physical and behavioural changes as

a result of these novel environments?

For example

there are birds which have changed the pitch of their calls or the time of

year that they lay their eggs. Some have

even completely stopped migrating.

My research

looks at the effect of urbanisation on wildlife, and to do this, I study

spiders.

They might

seem like an odd choice but spiders are the perfect model organism for this

research.

They are an

important component ecosystems through their predation on flies and other pest

species and are food resources for birds.

Also, they

are very diverse, and some, but not all, do particularly well in cities

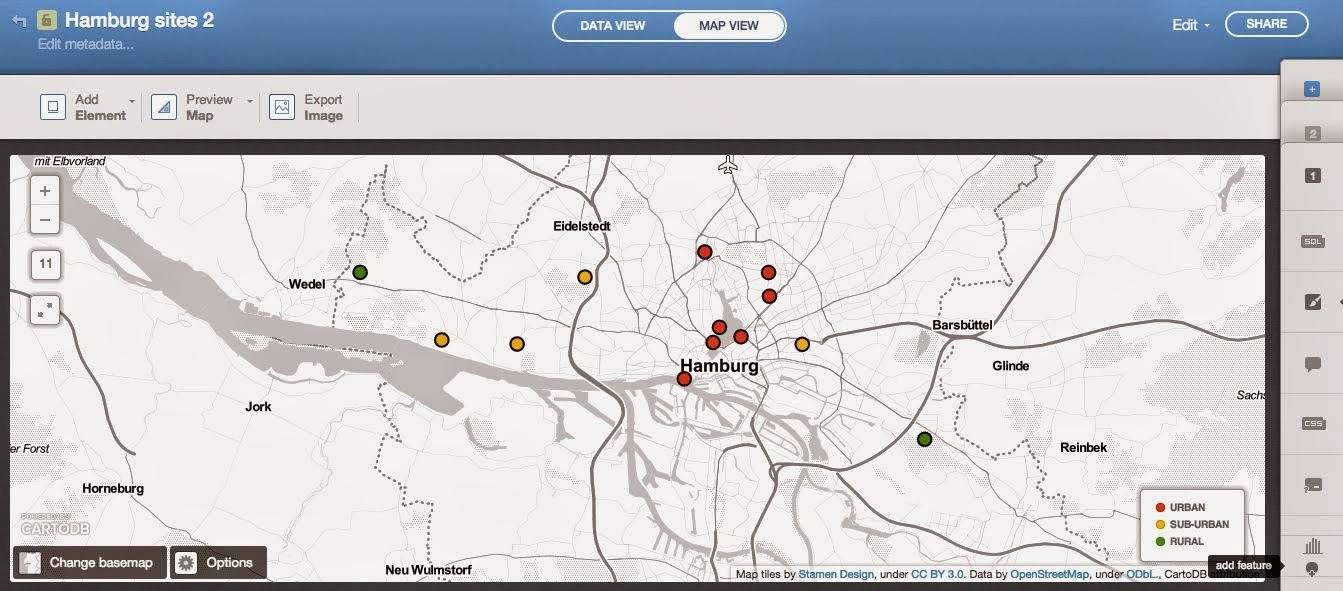

The first

step of my research was to find out which spiders are living in cities.

Imagine

your back garden, how many different types of spider do you think live in

there? Maybe some huntsmen and a red back?

I found an

average of 13 species, and up to 20 in some gardens.

Quite

amazing biodiversity, all of these spiders here are regulars in Sydney back

gardens.

Although

there were some spiders that were only found in natural areas, we see there are

many species that like cities.

To find out

why, I focused on these beautiful golden orb weavers which are common in the

Sydney area.

I found that

not only are there more of them closer to the city, but they are larger and

have increased reproductive capacity in urban areas.

They did

particularly well in areas with lots of concrete surfaces and manmade objects

So this is

an example of how some species can benefit from urbanisation.

I also

looked at whether spiders, like birds, are altering their behaviors in urban

areas.

I found

that spiders cities respond to stimulus differently to rural spiders. They are

less bold and less active.

This is evidence

that some spiders are altering the way they behave in order to survive in cities.

Through my

research, and the work done by other urban ecologists, we are gaining a better

understanding of the impacts of urbanisation on wildlife.

We can use

this knowledge to maintain biodiversity in cities, and create healthy,

functioning ecosystems in urban areas.

|

| Usyd 3MT finalists. Photo from The University of Sydney FB page |